ANOTHER EARTH:

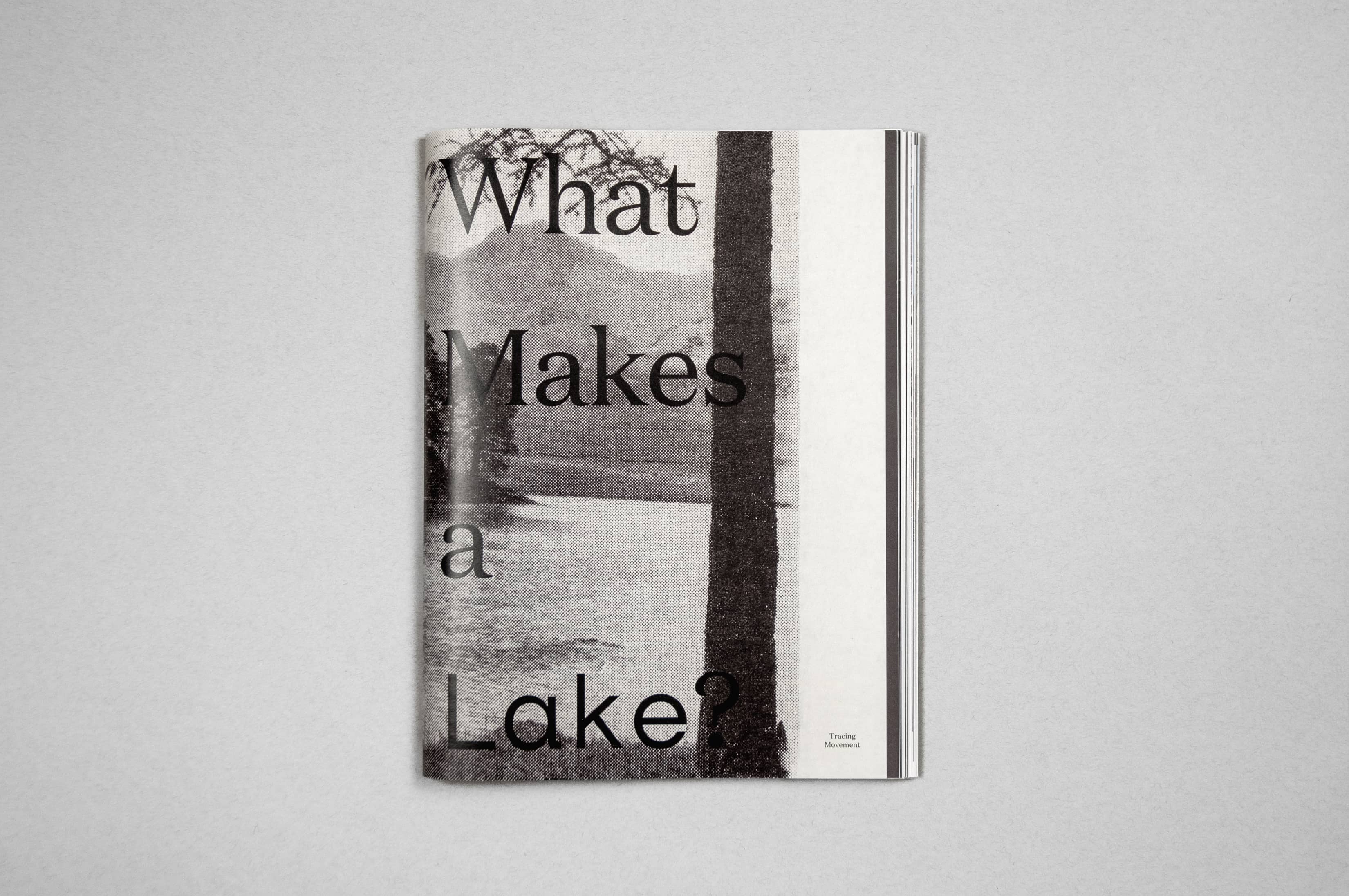

WHAT MAKES A LAKE?

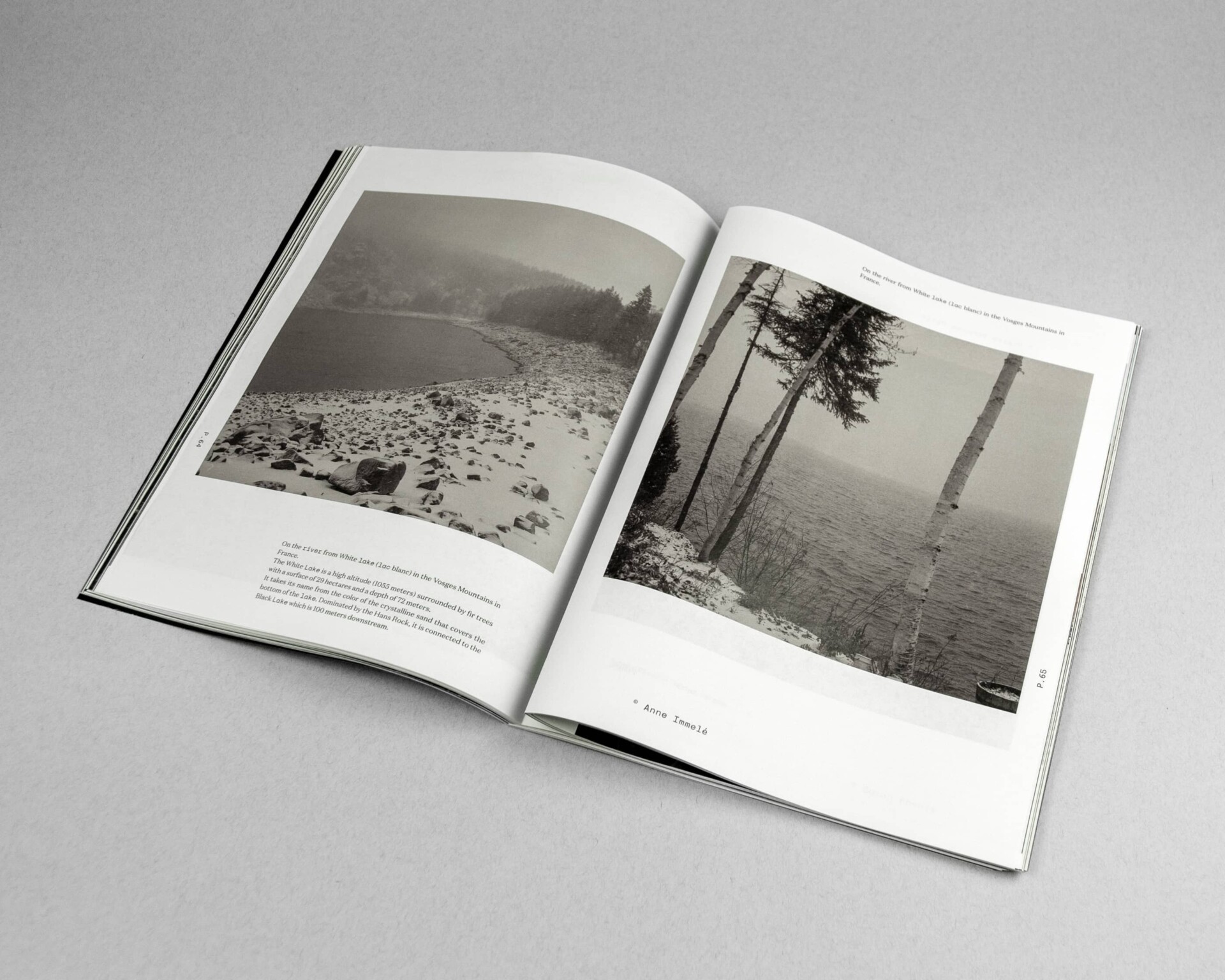

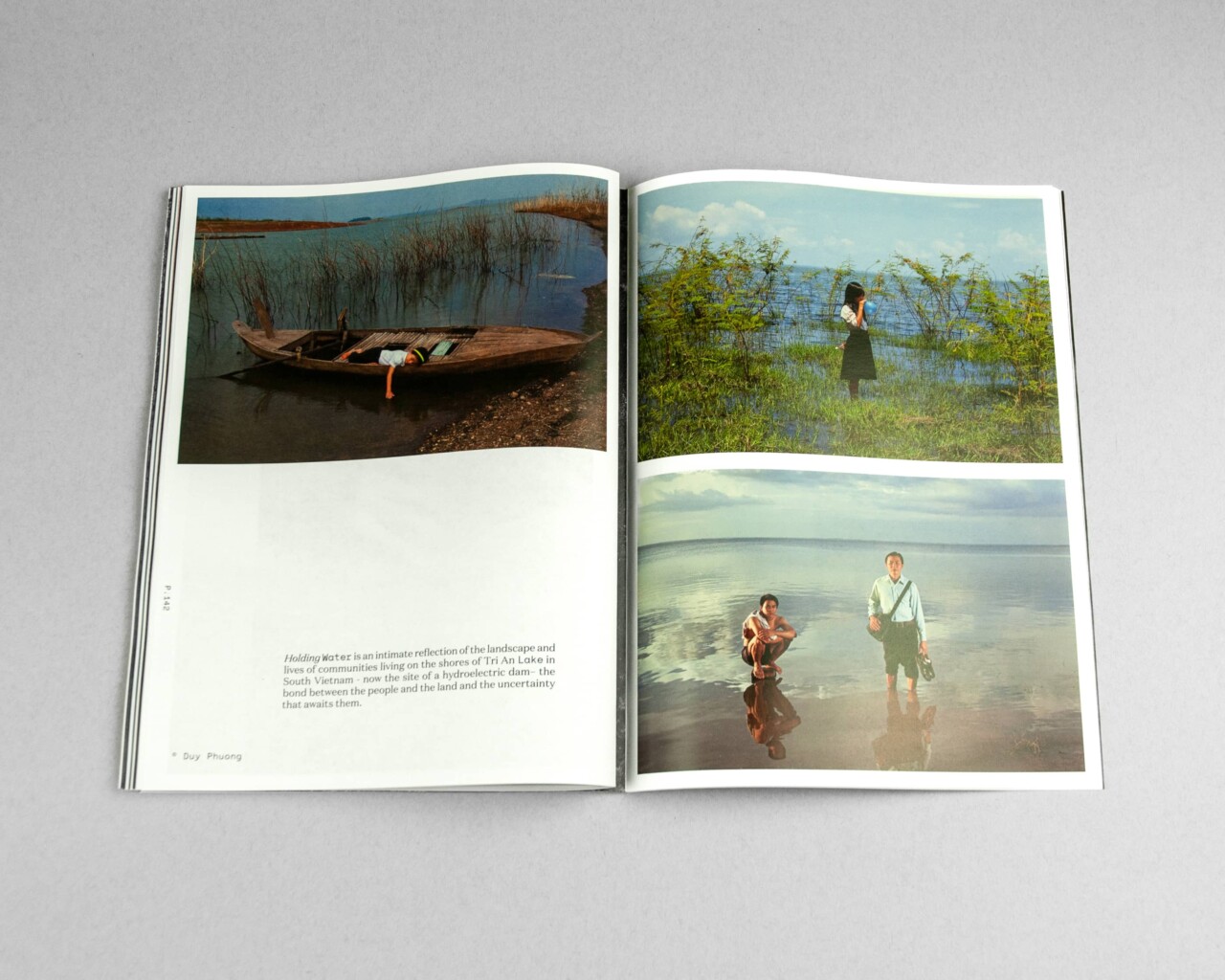

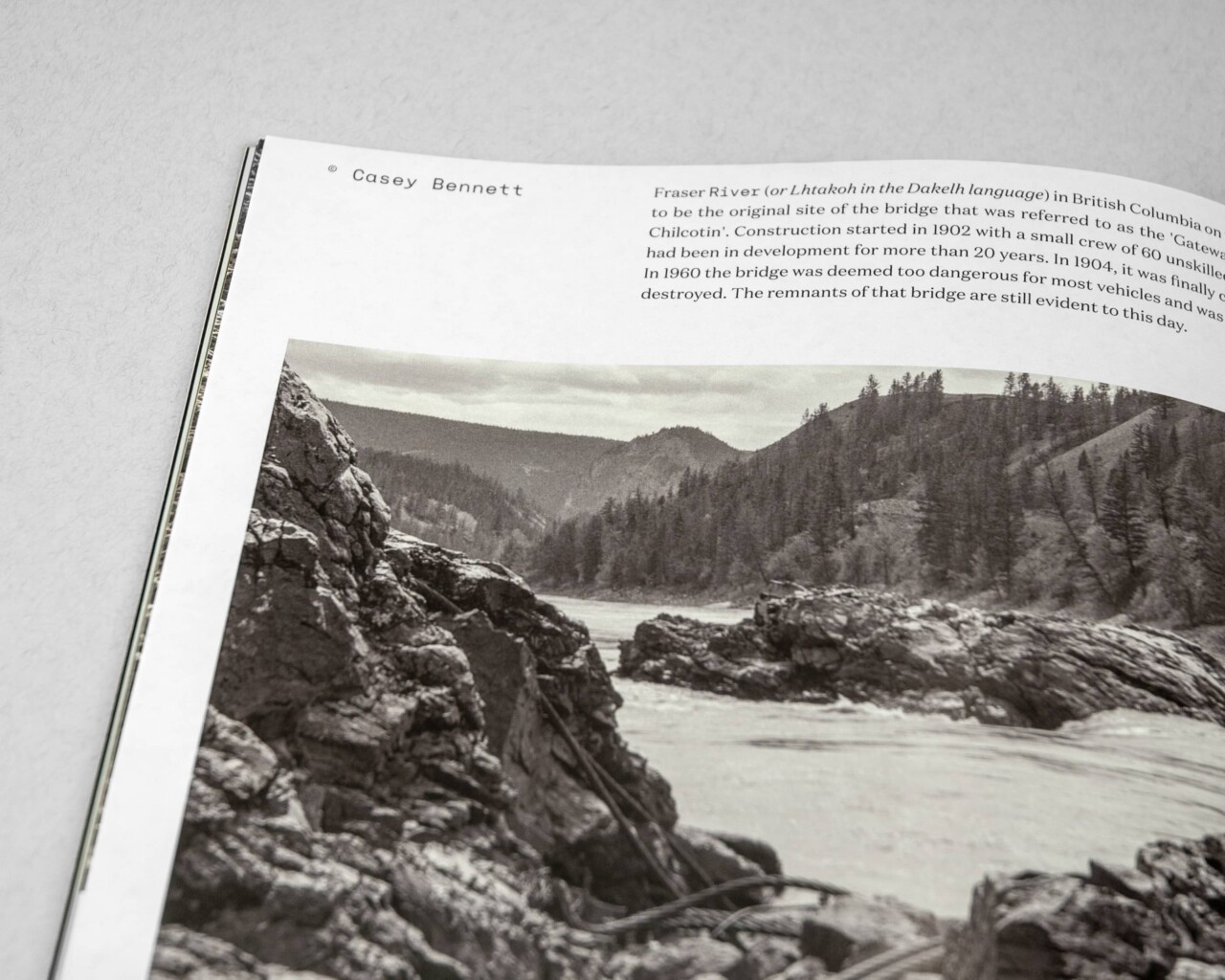

What Makes a Lake? brings together the work of more than 80 artists to create a portrait of Earth’s lakes, rivers, and oceans. This collection of images and text offers an intimate experience of places that we hope create a new connection and commitment to caring for our most vulnerable ecossytems.

Concept, curation, editing: Estefania Puerta and Abbey Meaker

Sequencing: Abbey Meaker and Cristian Ordóñez

Design: Cristian Ordóñez

Printer: The Gas Company (Toronto, Canda)

Publisher: Another Earth

The earth communicates in the presence and absence of lakes.

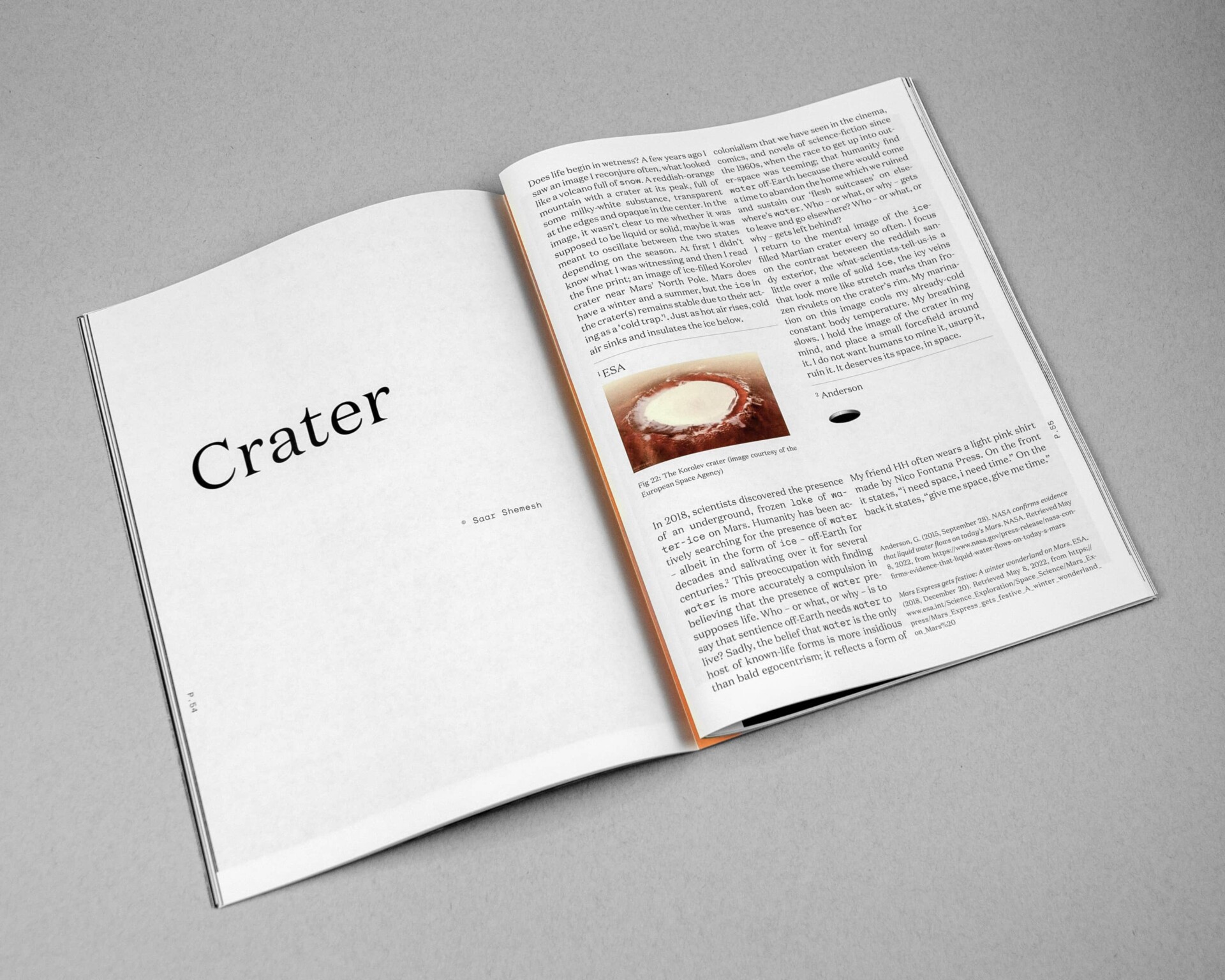

A lake is a large body of water surrounded by land. Lakes are formed by preceding natural events–glaciers, earth faults, the movement of tectonic plates. The craters of dormant volcanoes may fill with rain or melted snow, creating a lake. Sometimes the top of a volcano can collapse during an eruption, leaving a caldera which may also fill with rainwater and become a lake. Oregon’s Crater Lake was formed when the ancient volcano Mount Mazama’s cone collapsed.

Oxbow lakes are created when, during periods of flooding, a wide meander of a river is cut off, leaving a body of standing water. Its shape resembles the frame that fits over an ox’s neck when it’s harnessed to pull a wagon or a plow. Lakes are also created by landslides and mudslides. The debris that collects at the foot of hills and mountains create natural dams that block the flow of water, thereby forming a lake. Trees collected by beavers plug up rivers and streams creating large ponds and marshes. Habitat building creates lakes and new ecosystems.

A lake is what is left behind, a response, an imprint, a historical document of what came before. While lakes communicate the past, they also represent the present health of the planet and its communities. In a sense, lakes keep time. They are portals, storytellers, mirrors. Lakes are not simply bodies of water. They embody in implicit and explicit ways all of Earth’s ecosystems. They are the melted glaciers, the buckling and folding of the Earth’s crust, volcanoes, earthquakes, landslides. They are also what surrounds them: land, wetlands, bogs, floodplain forests and their respective flora and fauna. They are carnivorous plants and fungi, rocks that line their shores. We are the lake: our gaze, our histories, and memories.

- Abbey Meaker

What Makes a Lake? Tracing Movement began as a project about Lake Champlain–the lake that two of the publishers currently live near. We wanted to collect documentation around the lake’s health, history, stories, and imagery, to find a bridge between what we feel when we visit this grandiose body of water and what science warns us of the health of the lake itself. As time makes spaces for water to fill, we wanted to make a book that can capture a moment in this time, of our own filling.

It quickly became evident that to consider Lake Champlain, we must consider all the ways in which water flows in and out beyond our arbitrary borders. The body of water quickly turned into the veins extended into the wings of birds, minerals of stone, roots of plants, and stories told. We knew in order to talk about Lake Champlain, we really needed to open this up to other lakes around the world.

While we could never include every lake on earth, we submitted to the game of chance when it came to which lakes we did include. Through our open call, we received compelling work that opened the veins of the world to us and expanded the conversation into bigger questions around how we are all connected through these flowing currents and our natural tendency to seek water in moments of quiet meditation.

This publication is a collection of reflections when we consider how water affects our past, present and future. During our time here on earth, can we hear the water speak? More urgently, can we listen?

- Estefania Puerta

ANOTHER EARTH / BROTHER OF ELYSIUM:

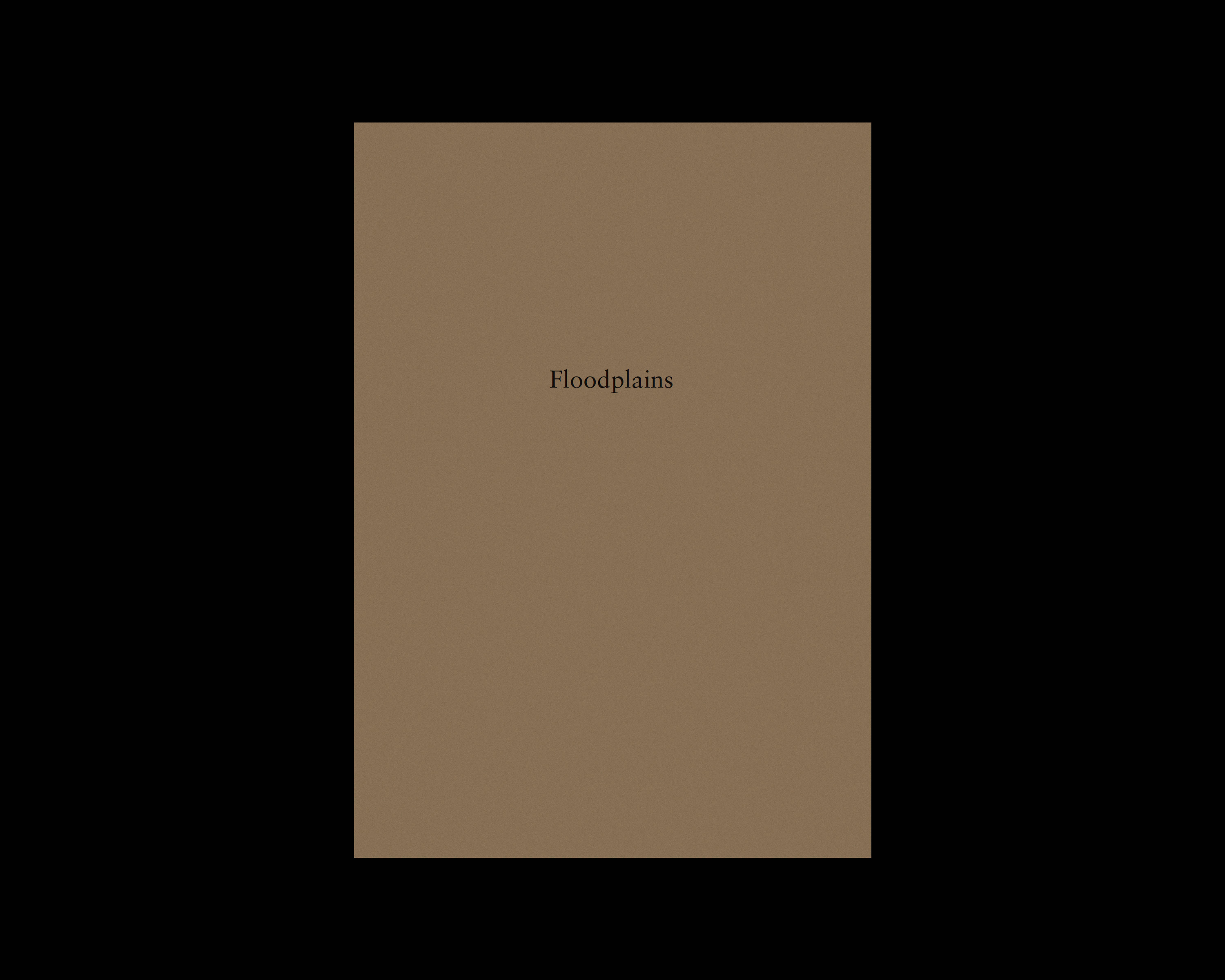

FLOODPLAINS BY ABBEY MEAKER

Floodplains is a book of photographs by Abbey Meaker made among the Silver Maple Floodplains Forests in Vermont, along the Winooski River, Derway Cove and the Hawkins Road Marsh during 2020-2021.

Floodplains is a book of photographs by Abbey Meaker made among the Silver Maple Floodplains Forests in Vermont, along the Winooski River, Derway Cove and the Hawkins Road Marsh during 2020-2021.

37 pages

6.5 x 9.25 inches

Sewn and bound

Letterpress printed dust jacket

Edition of 100 copies

English

Edited by Abbey Meaker and The Brother In Elysium.

Book design, binding and letterpress dust jacket by The Brother In Elysium.

All images were shot on film and printed digitally.

All images copyright Abbey Meaker.

Review: American Suburb X

ANOTHER EARTH:

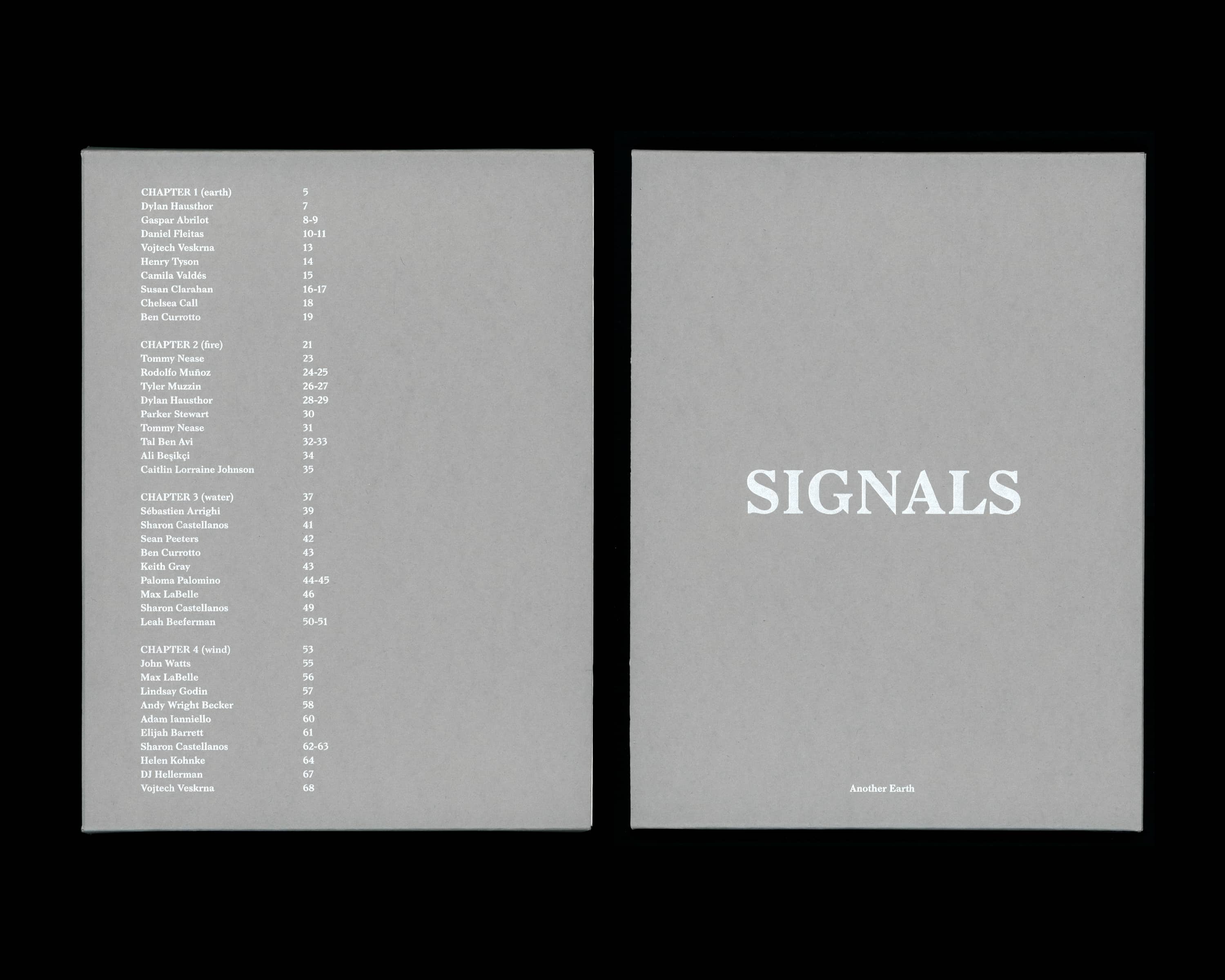

SIGNALS

Signals presents the images and words of 30 artists and writers as messages received from a beautiful and strained planet. Organized into elemental chapters - earth, fire, water, wind (air) - the works coalesce around weather events from the devastating to the mundane, offering a collective portrait of reciprocity and communication / communion between self, earth, and environment.

Concept, copy, editing: Abbey Meaker

Curation, editing, sequencing: Abbey Meaker and Cristian Ordóñez

Design: Cristian Ordóñez

Printer: The Gas Company (Toronto, Canda)

Publisher: Another Earth

ANOTHER EARTH:

LAND CHAPTERS

This book is an integral part of the exhibition, Land Chapters, held on a rural Vermont property in June 2021. Participating artists made land-based installations, esssays, photographs, field recordings and composiions in response to the natural enviroments around them. The book is one of three spaces in which work from the project is experienced; the others are ephemeral on the land, and sound on cassette.

Concept, copy writing and editing: Abbey Meaker and Estefania Puerta

Curation, editing: Abbey Meaker and Estefania Puerta

Design Concept and sequencing: Cristian Ordóñez

Printer: Vid Press (Toronto, Canda)

Publisher: Another Earth

ARTIST FIELD:

LAND CHAPTERS

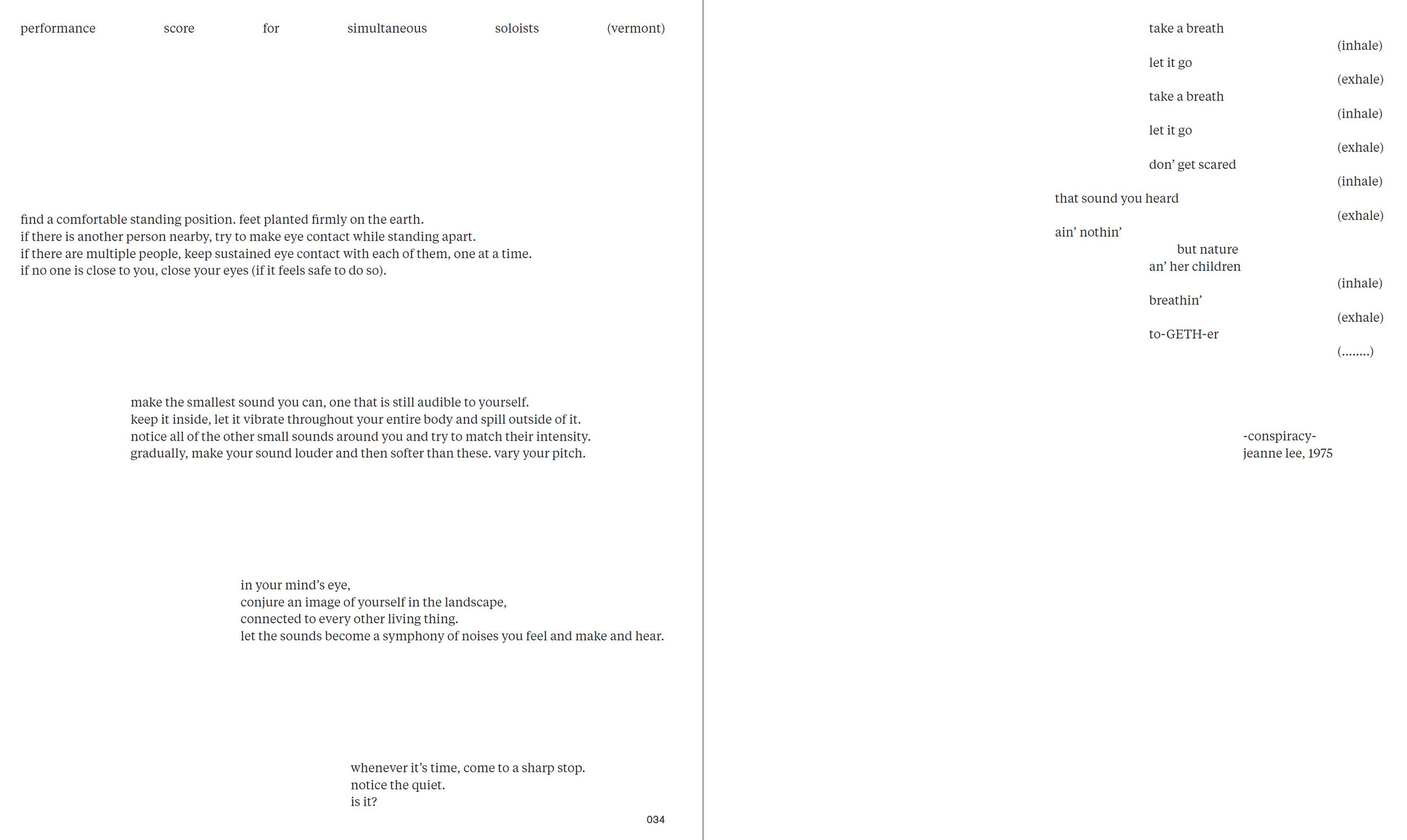

LAND CHAPTERS was an exhibition that included a series of land-based installations in Richard, Vermont; an artist book of photographs, essays, and scores; and a tape of environmental field recordings and compositions.

Curated by Estefania Puerta and Abbey Meaker, the show brought together 16 artists and writers to respond to their own natural environments, with the exhibition site functioning as a stand-in and backdrop.

Participating artists: Sonia Louise Davis, Ivan Forde, Chief Shirly Hook, Alan Huck, Wren Kitz, Wes Larios, Travis Klunick, Angus McCullough and Ashlin Dolan, Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya, Brian Raymond, Jordan Rosenow, Rachel Vera Steinberg, Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri, Devin Alejandro Wilder, and Stephanie Wilson

Read interview of curators on AUTRE

Curated by Estefania Puerta and Abbey Meaker, the show brought together 16 artists and writers to respond to their own natural environments, with the exhibition site functioning as a stand-in and backdrop.

Participating artists: Sonia Louise Davis, Ivan Forde, Chief Shirly Hook, Alan Huck, Wren Kitz, Wes Larios, Travis Klunick, Angus McCullough and Ashlin Dolan, Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya, Brian Raymond, Jordan Rosenow, Rachel Vera Steinberg, Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri, Devin Alejandro Wilder, and Stephanie Wilson

Read interview of curators on AUTRE

When we set out to organize Land Chapters, we knew we wanted to explicitly address the human relationship to nature. Immediately that intention unearthed a large and murky web of the ways in which we categorize human, nature, and relationship.

Instead of trying to constrict a boundary around these terms, we welcome their impossibility of being tamed into a cohesive experience. In fact, the need to categorize these terms has historically erased many peoples’ and species’ stories, experiences, and complexities of survival and continuation. It has silenced the small creek into a roaring paper mill, it has given European names to mountains that were given names by their protectors and story keepers.

Here in Vermont, one of the region’s greatest mountains known today as Camel’s Hump was given the original name of Tawapodiiwajo, Abenaki for “mountain seat,” alluding to traditional stories of the hero Glooscap using the mountain as his personal seat. Tabaldak gave Glooscap the power to create a good world. Glooscap learned that hunters who kill too much would destroy the ecosystem and the good world he had sought to create and went on to seek the advice of Grandmother Woodchuck (Agaskw) who then plucked all the hairs out of her belly (hence the lack of hair on a woodchuck's belly) and wove them into a magical bag for Glooscap to use and eventually learn the lesson that they needed to hunt to remain strong.

What other stories and histories are layered in these names, re-namings, un-namings? How do we resist adding a new boundary to the terms that have spliced our lives into multitudes of subjugation? What if locating yourself in nature is not about place at all but about memory, perception, sound, proposals, movement?

Instead of trying to constrict a boundary around these terms, we welcome their impossibility of being tamed into a cohesive experience. In fact, the need to categorize these terms has historically erased many peoples’ and species’ stories, experiences, and complexities of survival and continuation. It has silenced the small creek into a roaring paper mill, it has given European names to mountains that were given names by their protectors and story keepers.

Here in Vermont, one of the region’s greatest mountains known today as Camel’s Hump was given the original name of Tawapodiiwajo, Abenaki for “mountain seat,” alluding to traditional stories of the hero Glooscap using the mountain as his personal seat. Tabaldak gave Glooscap the power to create a good world. Glooscap learned that hunters who kill too much would destroy the ecosystem and the good world he had sought to create and went on to seek the advice of Grandmother Woodchuck (Agaskw) who then plucked all the hairs out of her belly (hence the lack of hair on a woodchuck's belly) and wove them into a magical bag for Glooscap to use and eventually learn the lesson that they needed to hunt to remain strong.

What other stories and histories are layered in these names, re-namings, un-namings? How do we resist adding a new boundary to the terms that have spliced our lives into multitudes of subjugation? What if locating yourself in nature is not about place at all but about memory, perception, sound, proposals, movement?

Echoing the first generation of land artists who used earth matter to make their work, we have invited artists to consider the ways in which we influence and are influenced by “the land.”

Rather than impose an intervention, we encouraged an anti-heroic response: an embrace, dialogue, and open exploration, not just of this particular piece of land with its own storied history, but to all natural environments that keep us in the mire of speculation when it comes to what we deem natural environments. The work included in this exhibition is on unceded land of the Abenaki Nation and also brings into focus territories across North America and abroad including the Mexican-US border, Puerto Rico, and Italy.

There is no fixed sequence to this exhibition to guide you from one point of experience to the next. Rather, each work included is to be viewed as a point on a map that unfurls itself into different responses to our curatorial prompt; a map with no one name but many names, lands without borders, experiences without dogma.

We live in a different era of earth collapse than the land artists who preceded us. Romanticizing our connection to nature can feel patronizing to a dying earth and species. In place of romance as an answer, we believe this work offers nature as a question. We believe this work pushes against the instinct to other and fetishize nature, that it instead engenders curiosity, posing a question rather than an answer.

We hope this project finds its way into your own relationship with the world(s) around and within you.

Estefania Puerta and Abbey Meaker, 2021

Rather than impose an intervention, we encouraged an anti-heroic response: an embrace, dialogue, and open exploration, not just of this particular piece of land with its own storied history, but to all natural environments that keep us in the mire of speculation when it comes to what we deem natural environments. The work included in this exhibition is on unceded land of the Abenaki Nation and also brings into focus territories across North America and abroad including the Mexican-US border, Puerto Rico, and Italy.

There is no fixed sequence to this exhibition to guide you from one point of experience to the next. Rather, each work included is to be viewed as a point on a map that unfurls itself into different responses to our curatorial prompt; a map with no one name but many names, lands without borders, experiences without dogma.

We live in a different era of earth collapse than the land artists who preceded us. Romanticizing our connection to nature can feel patronizing to a dying earth and species. In place of romance as an answer, we believe this work offers nature as a question. We believe this work pushes against the instinct to other and fetishize nature, that it instead engenders curiosity, posing a question rather than an answer.

We hope this project finds its way into your own relationship with the world(s) around and within you.

Estefania Puerta and Abbey Meaker, 2021

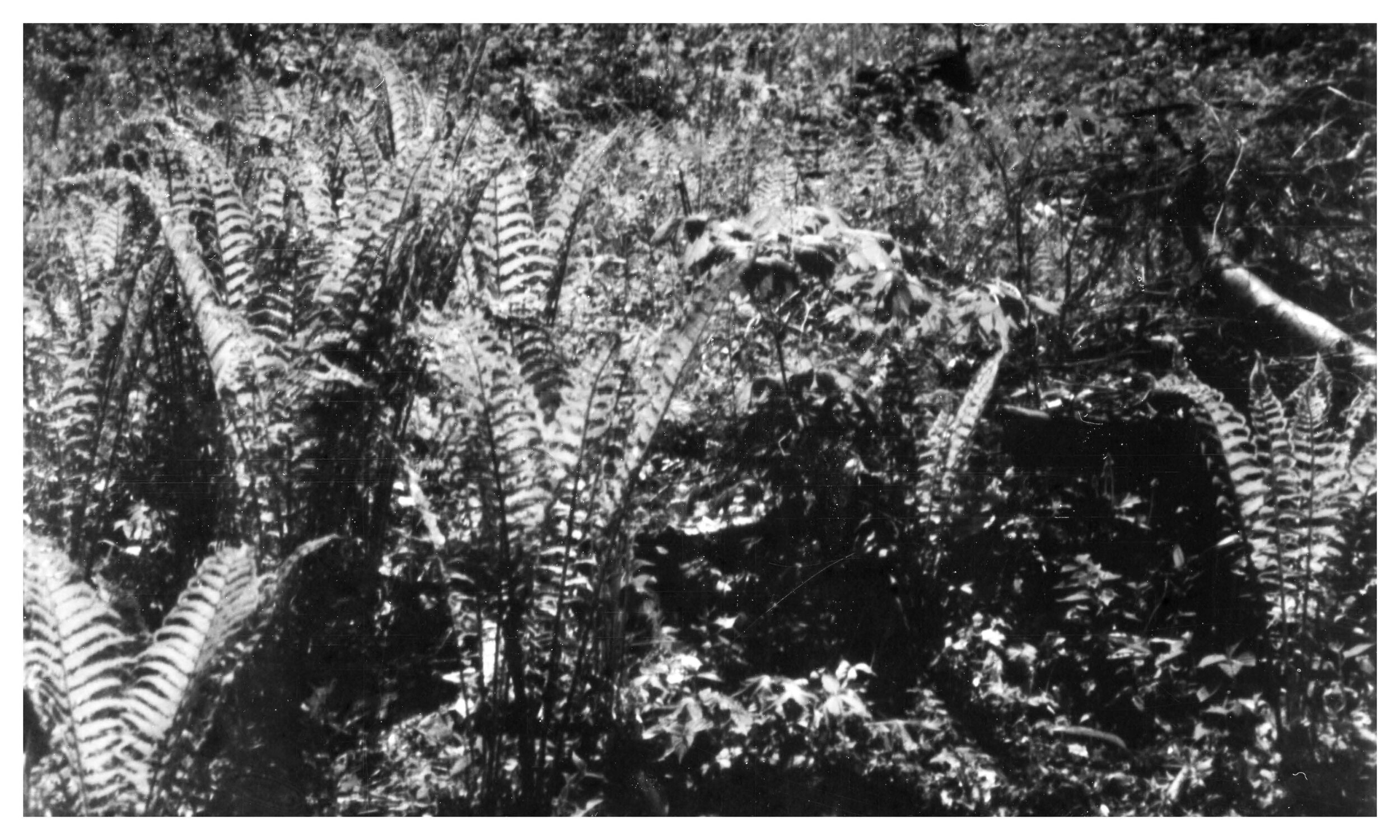

LAND INSTALLATIONS

Artists from across the U.S. installed pieces that were a direct response to the land they inhabit, then installed within the 40 acres of land in Richmond, Vermont. The land itself is a dense forested area that has been logged and is wet so ferns, brambles, young trees, fungi, porcupine, deer, coyotes, salamanders, and many species of birds have all found a home here.

Ranging from interactive experiences (Contact Kit) to proposals for collaboration with our natural resources (Sun Belly), the work in the exhibition opene up different possibilities for how we encounter our natural surroundings and a built environment (Four by Eight, Old Bones That Turn to Ziploc Bags and Sewage Tubing). While some of these works briefly inhabited the Beaver Pond Hill property during the duration of the exhibition, other works have truly become a part of the environment and beckon us to question the long term effects of moving earth matter, beings, and histories into new lands (Transplante, Cascara de Cascabel).

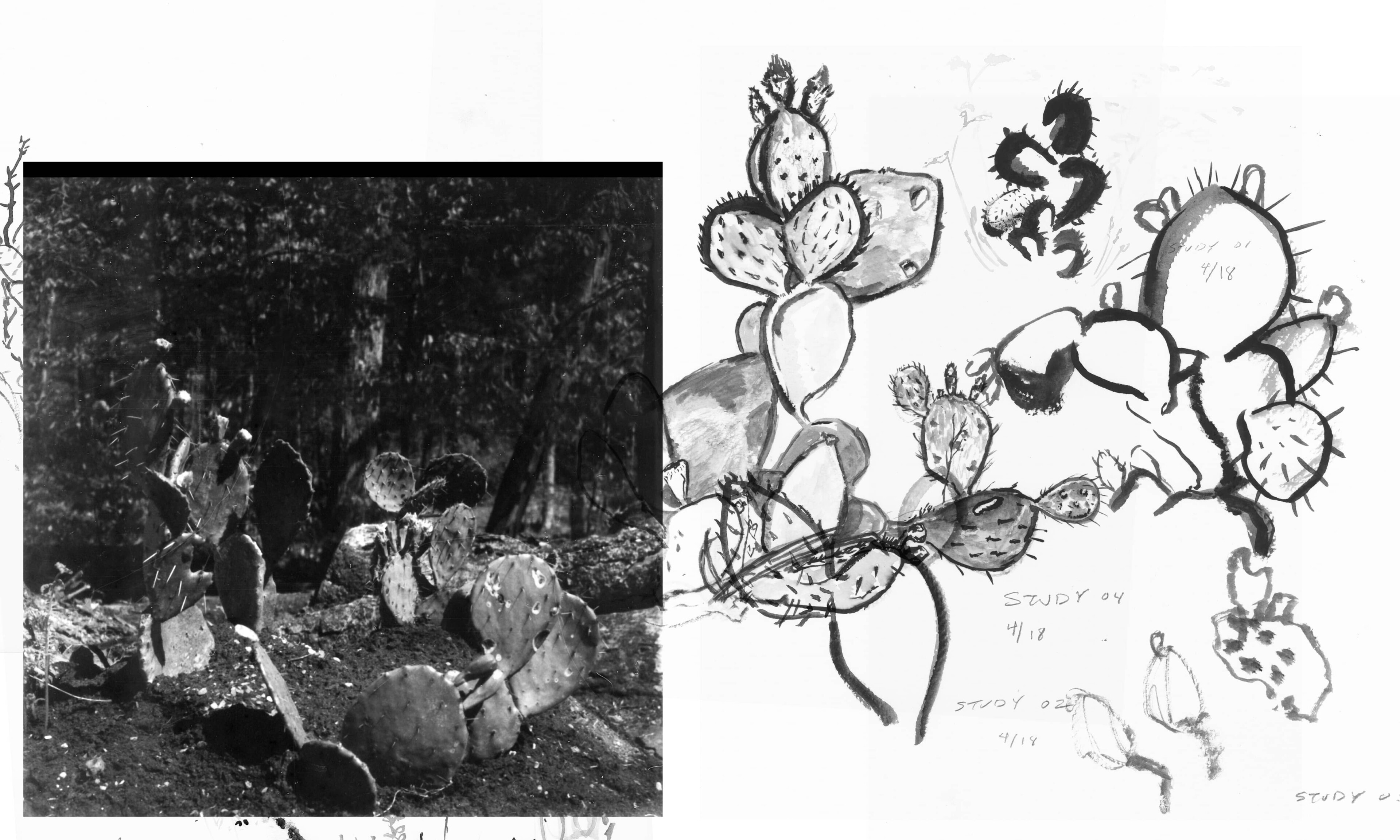

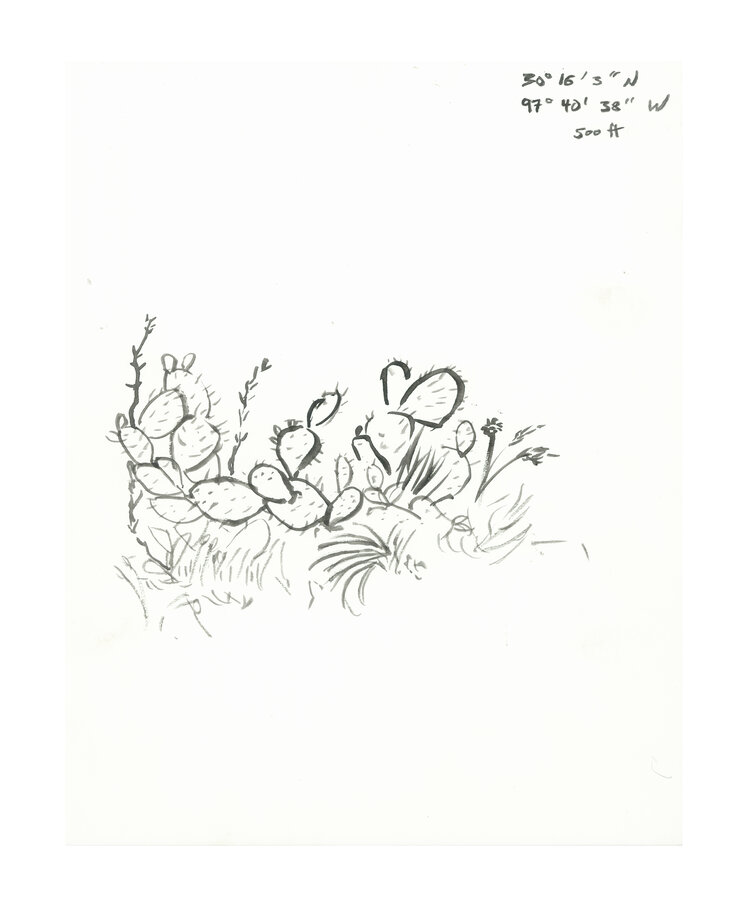

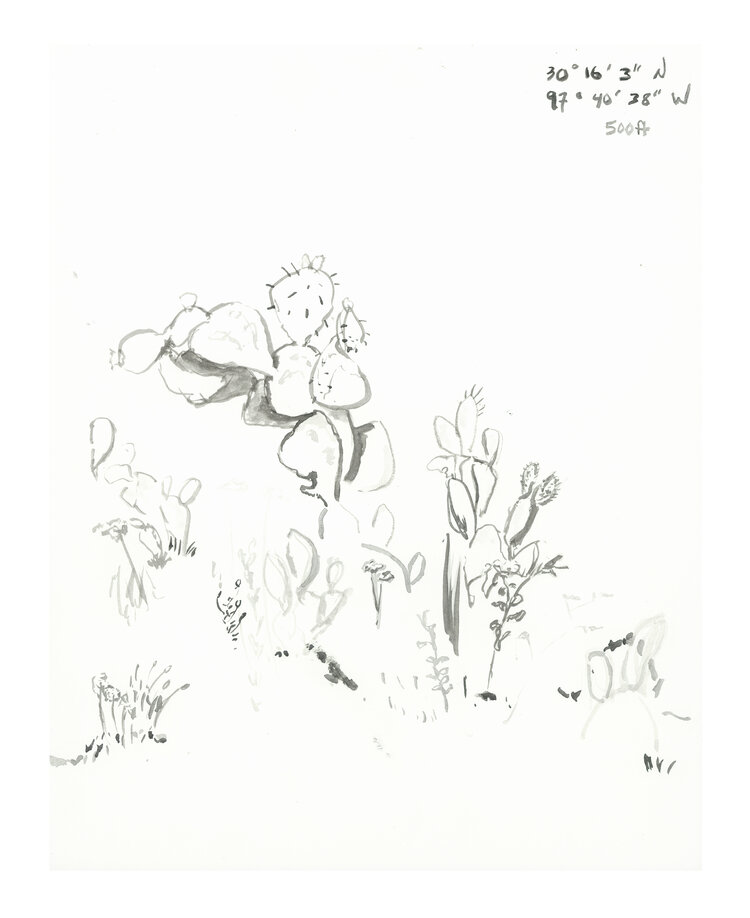

Devin Alejandro-Wilder

T R A N S P L A N T

Nopales / Opuntia engelmannii var. lindheimeri, soils (native and mixed), pea gravel, rocks, cardboard.

For Devin, "this process of transplanting cacti acts not only as a physical metaphor for the latinx diasporic experience, but also speaks to the literal practice of integrating non-native plants into radically non-native (even fully-opposing) environments— whether that be for presentation or preservation."

August, 2021 log from Este: The cacti are thriving on the land with new pads growing new pads. It is still contained within the stone wall boundary we made for it. It is unclear whether animals have tried nibbling at the pads, a couple of marks that resembled nibbles were on a pad or two. It seems like nothing really wants to eat it. We plan on harvesting some pads and eating them ourselves before the frost comes.

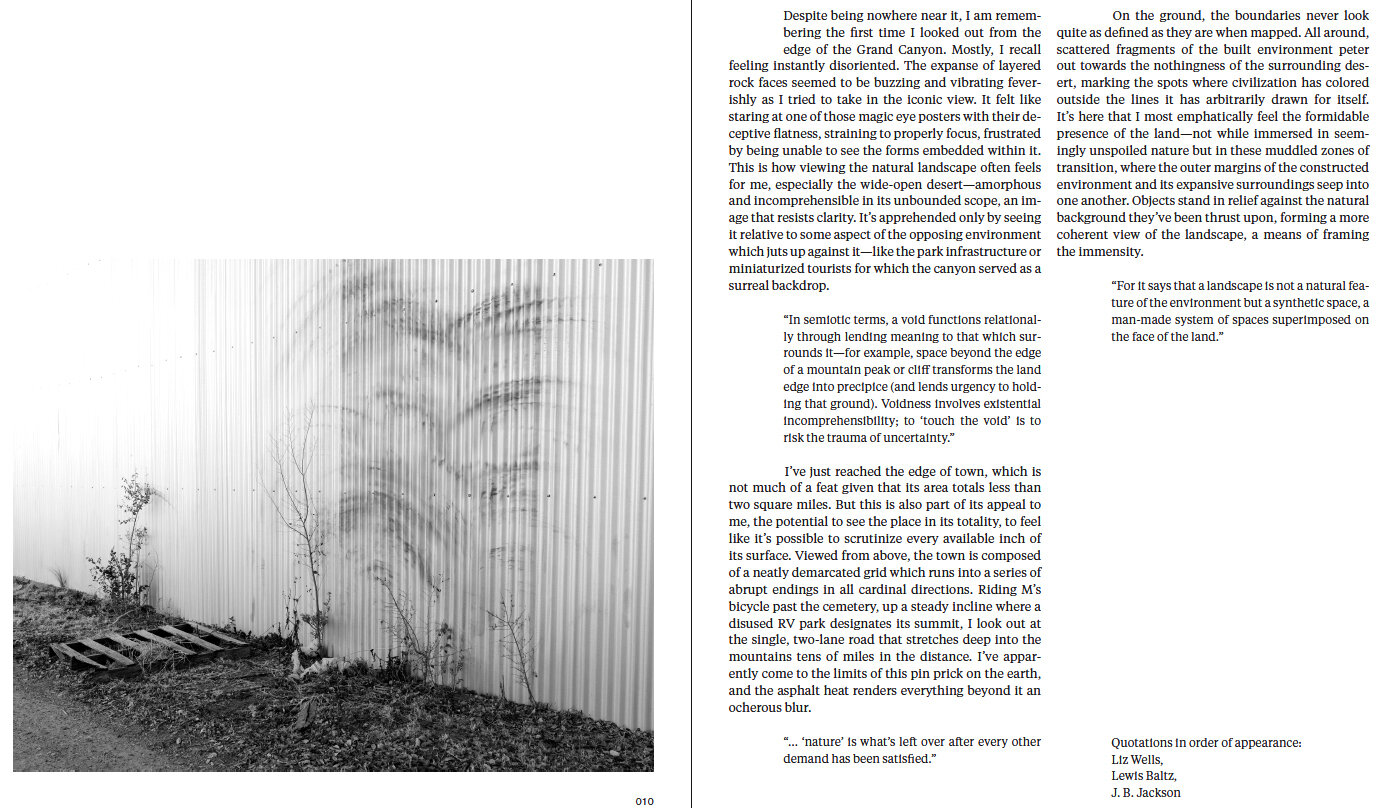

Jordan Rosenow

FOUR BY EIGHT

Galvanized corrugated steel, rebar

4 x 8 z 4 foot units

Four By Eight

Is the structure too strong? Has it dominated long enough?

Can it be undone?

Can it be replaced with trees? Fresh air?

Is there wiggle room?

Can it dance?

Can it love?

A structure can be as violent as any other thing

Race was built

Gender was built

Class was built

Endlessly built with the intent to dominate, endlessly

Is the structure too strong? Has it dominated long enough?

Can it be undone?

Can it be replaced with trees? Fresh air?

Is there wiggle room?

Can it dance?

Can it love?

A structure can be as violent as any other thing

Race was built

Gender was built

Class was built

Endlessly built with the intent to dominate, endlessly

This very land, these very trees, were once stolen and then again ravaged for lumber

This work is made with that in mind

With metal in mind

With walls and a roof in mind

With rigid structures in mind

With the hope of instability

Can it live outside of structure?

Can the material glisten?

Can it be soft?

Can it move freely?

Can it bring joy?

Can it disappear, gladly?

This work is made with that in mind

With metal in mind

With walls and a roof in mind

With rigid structures in mind

With the hope of instability

Can it live outside of structure?

Can the material glisten?

Can it be soft?

Can it move freely?

Can it bring joy?

Can it disappear, gladly?

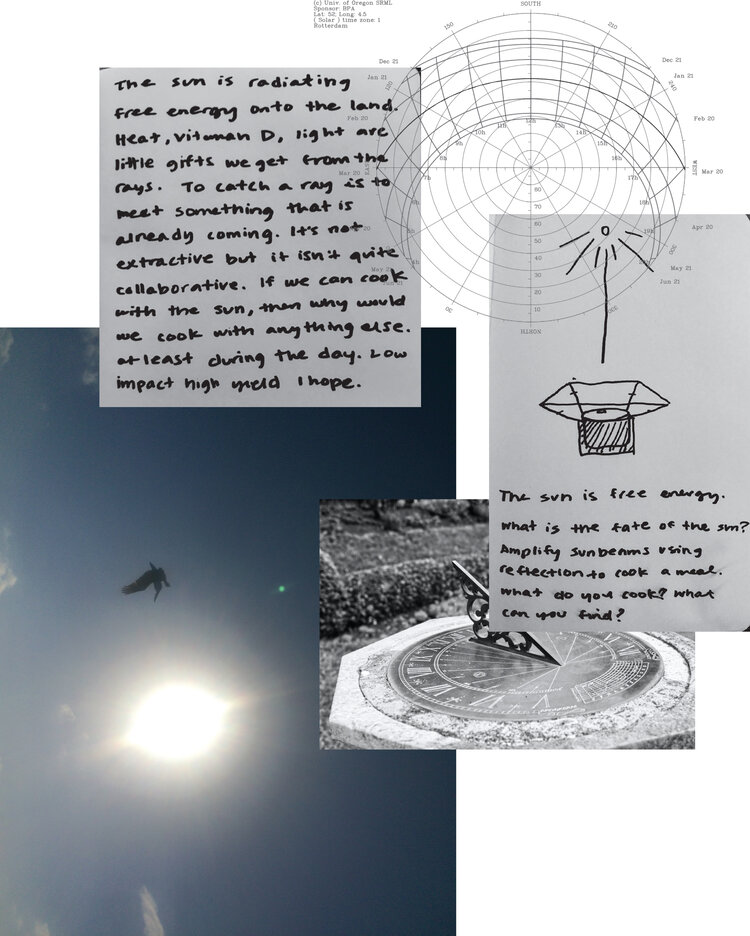

Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri

SUN BELLY: THE BIG STAR THAT FEEDS US

Mixed wood scrap, aluminum, paint, and plaster

Sun stew

A recipe depending on the season and the sun is a forgiving recipe. This is not a precise recipe but one to get creative with. I recommend that you start it in the morning, a few hours before you are hungry so that you can enjoy the process.

- 2 Cups green lentils or white beans soaked overnight

- 3 Shallots sliced thinly in crescents

- 1 1/2 teaspoon olive oil

- 2 Carrots

- Foraged ramps or mushrooms

- Spices depend on what you find but the foraged food should be the main flavor

- Salt and hot sauce to taste

Directions

- If it isn't already placed, set up the oven and let it start to warm.

- While it is warming, take a 20-minute walk and see what is growing. If it rained recently lookout for mushrooms. If it is springtime there may be ramps! The land will determine much of your meal. Pick some plants that you know are edible and are excited to eat.

- When you return to the oven it should be warm. Add in some olive oil into the pot followed by the shallots about 2 minutes later.

- Then add in the foraged items and stir. This is where I add herbs or spices.

- Once warm and aromatic, add in the soaked lentils or beans and 5 cups of water, carrots, some salt, and let cook.

- Salt to taste and garnish with some lemon and fresh herbs if they are in season.

Sun Bread

- 2 1/3 cups flour

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon active dry yeast

- 1 Teaspoon olive oil

- 1 cup lukewarm water

Directions

- Let the oven heat up in the sun and place the cup of water inside.

- Combine olive oil, yeast, and water and let sit for 4 minutes then mix in with the flour and salt.

- Let sit for 15 minutes and then knead. Once stretchy (3 or 4 minutes) let sit and rise for 3-4 hours.

- While you are waiting. Go for a walk and see if there is anything to forage to add to the top of your bread. Hopefully, you find some mushrooms or ramps.

- Before baking the dough, roll out with some flour and place on a baking sheet. Top with olive oil and salt (and foraged items if there are any).

- Place in the oven and bake! Timing will depend on the intensity of the sun that day so keep an eye on it.

- Enjoy fresh out of the oven with the sunlight falling on your body.

Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya

1. “TRES TRISTES GALLOS PA EL CALDO DE LAS TRES DE LA TARDE”, Yucca husk.

2. “Cascara de cascabel,” yucca husk.

3. “Old bones that turn to ziploc bags and sewage tubing,” Yucca husk, cat skull found when I was depressed on my birthday, zip ties, tiger toy, bones of a dog (maybe), plumbing tube.

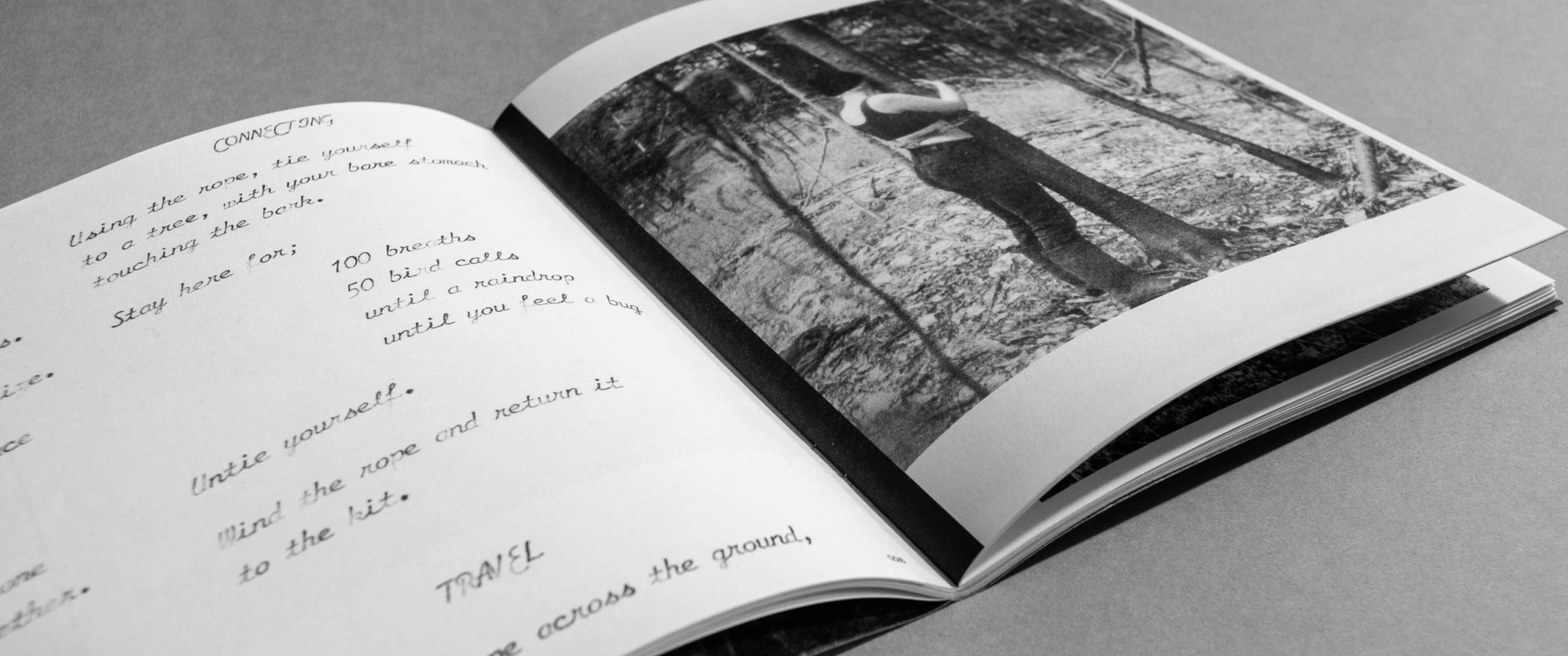

Angus McCullough and Ashlin Dolan

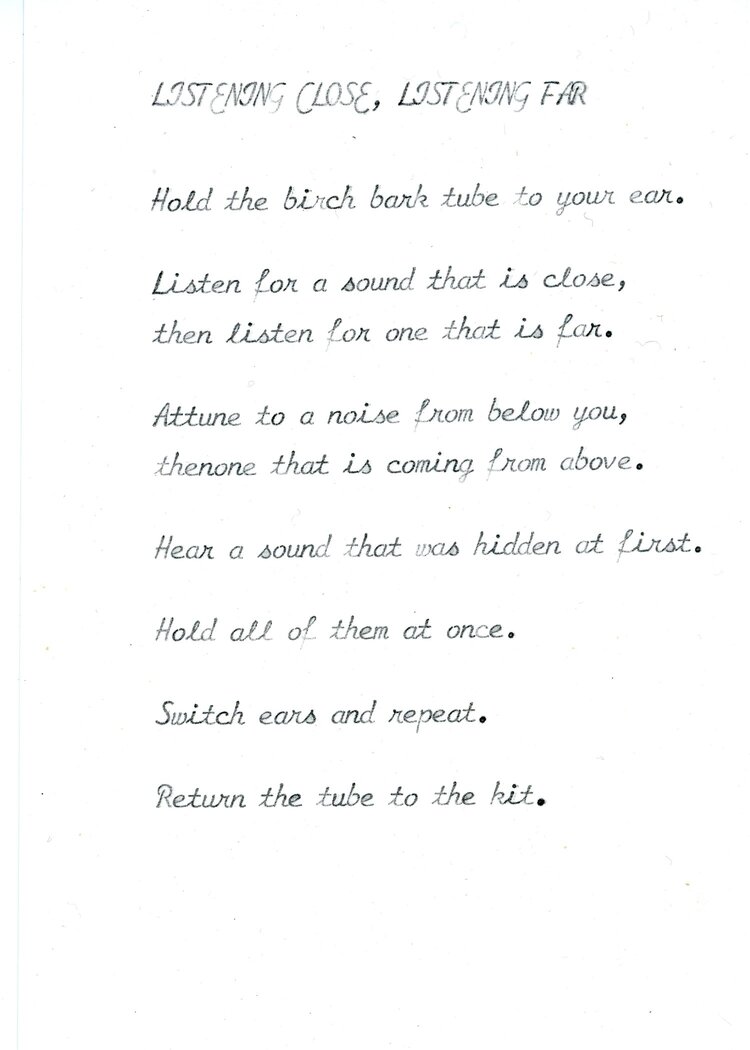

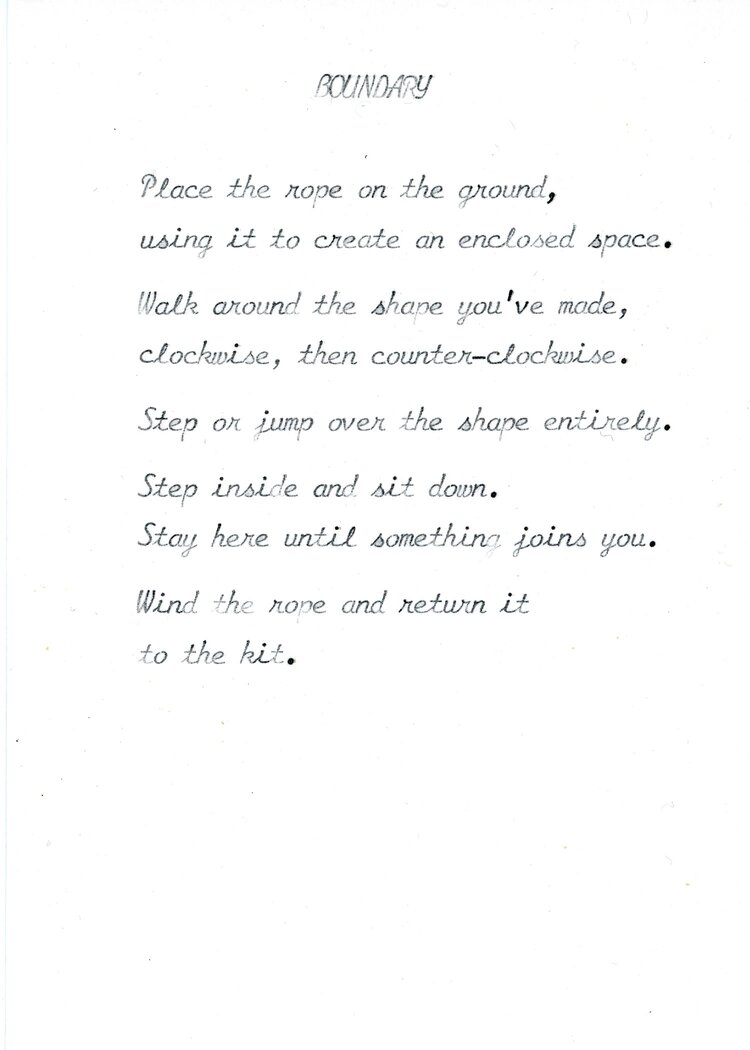

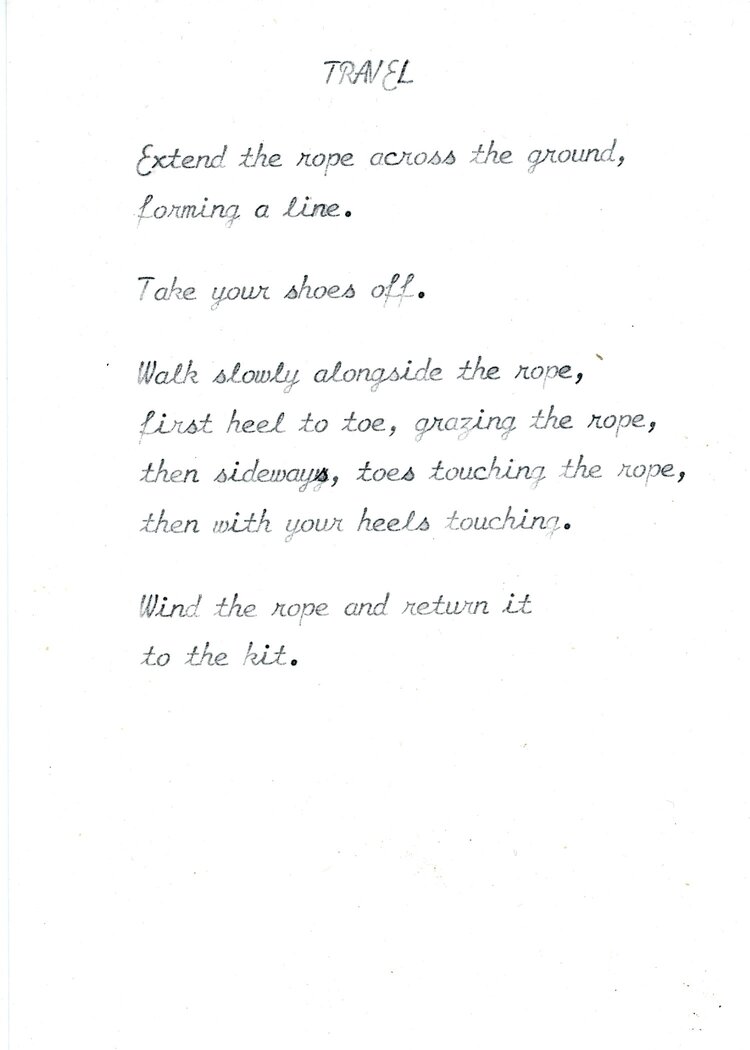

CONTACT KIT

Birch bark, grape vine, stone, moss, typed instructions in a plywood case

Chief Shirly Hook

TWO POEMS

photos by Abbey Meaker

photos by Abbey Meaker Alan Huck

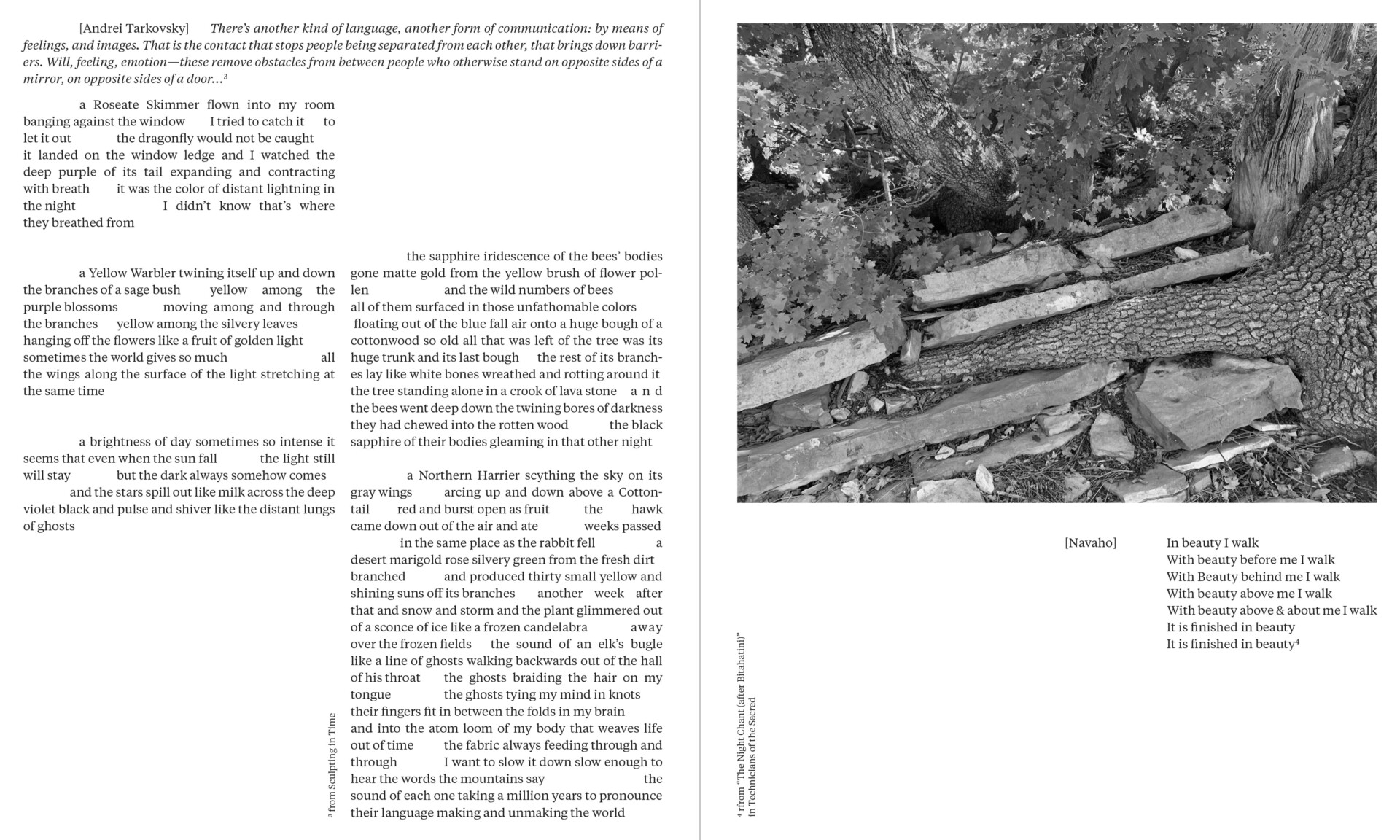

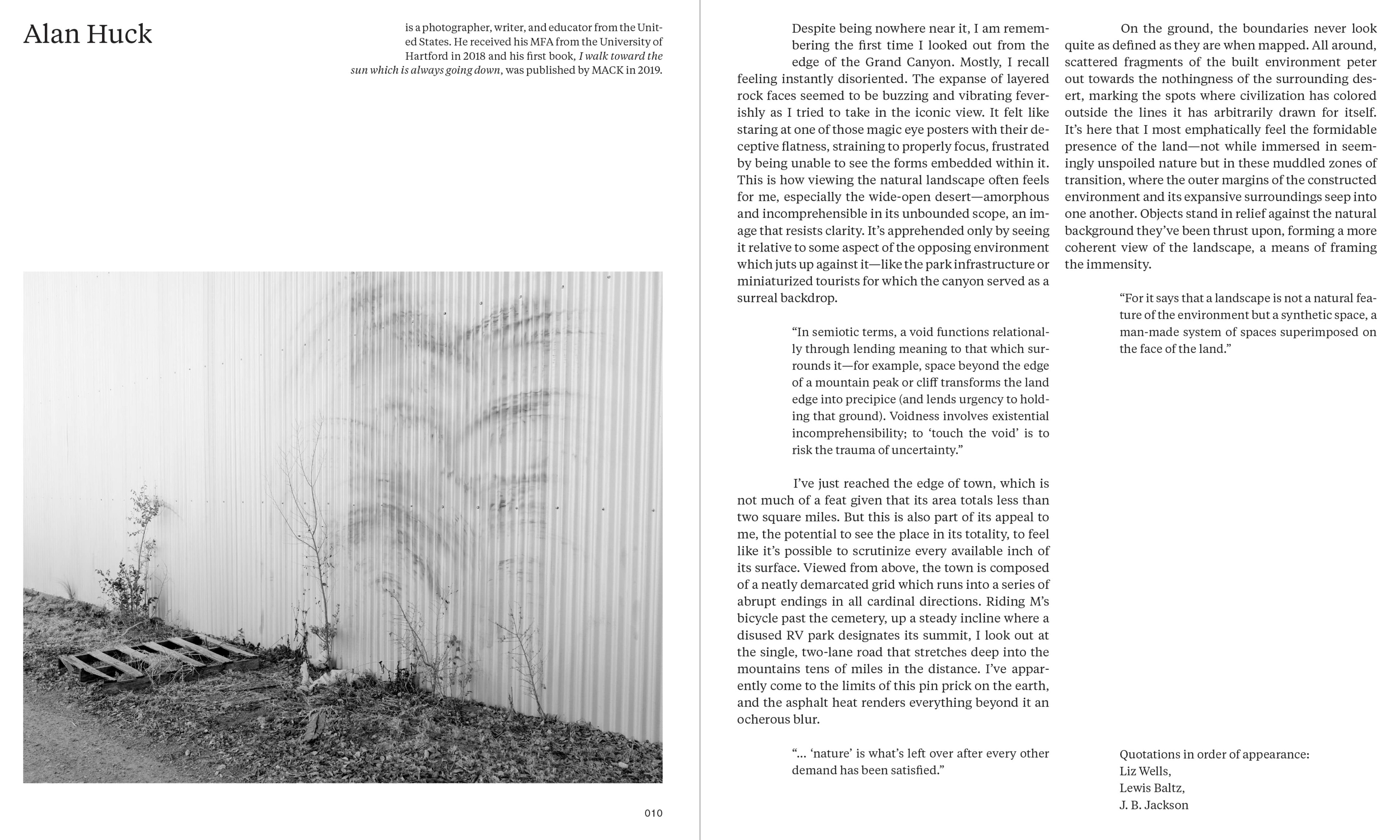

photos and text by Alan Huck

Wes Larios

Sonia Louise Davis

Travis Klunick

photographs and text by Travis Klunick

Rachel Vera Steinberg